Jordan Crowley was born with only one shrunken kidney to clean his blood. As he gets older, his one kidney gets sicker.

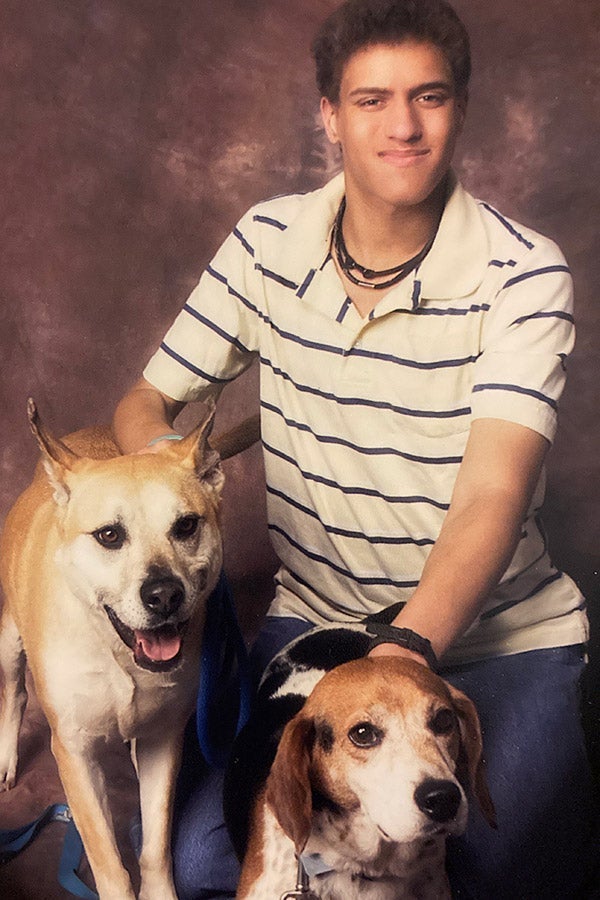

Jordan is now 18, loves dogs, and is more interested in telling me about his college classes than the fact that he was recently hospitalized for seizures, a complication of his illness. He’ll need a kidney transplant soon. He would be closer to getting that kidney transplant, if only he were categorized as white.

A patient’s level of kidney disease is judged by an estimation of glomerular filtration rate, or eGFR, which normally sits between 90 and 120 in a patient with two healthy kidneys. In the United States, patients can’t be listed for a kidney transplant until they’re deemed sick enough—until their eGFR dips below a threshold of 20.

Jordan is biracial, with one Black grandparent and three white ones. His estimated GFR depends on how you interpret this fact: A white Jordan has a GFR of 17—low enough to secure him a spot on the organ waitlist. A Black Jordan has a GFR of 21.

Jordan’s doctors decided he is Black, meaning he doesn’t qualify. So now, he has to wait.

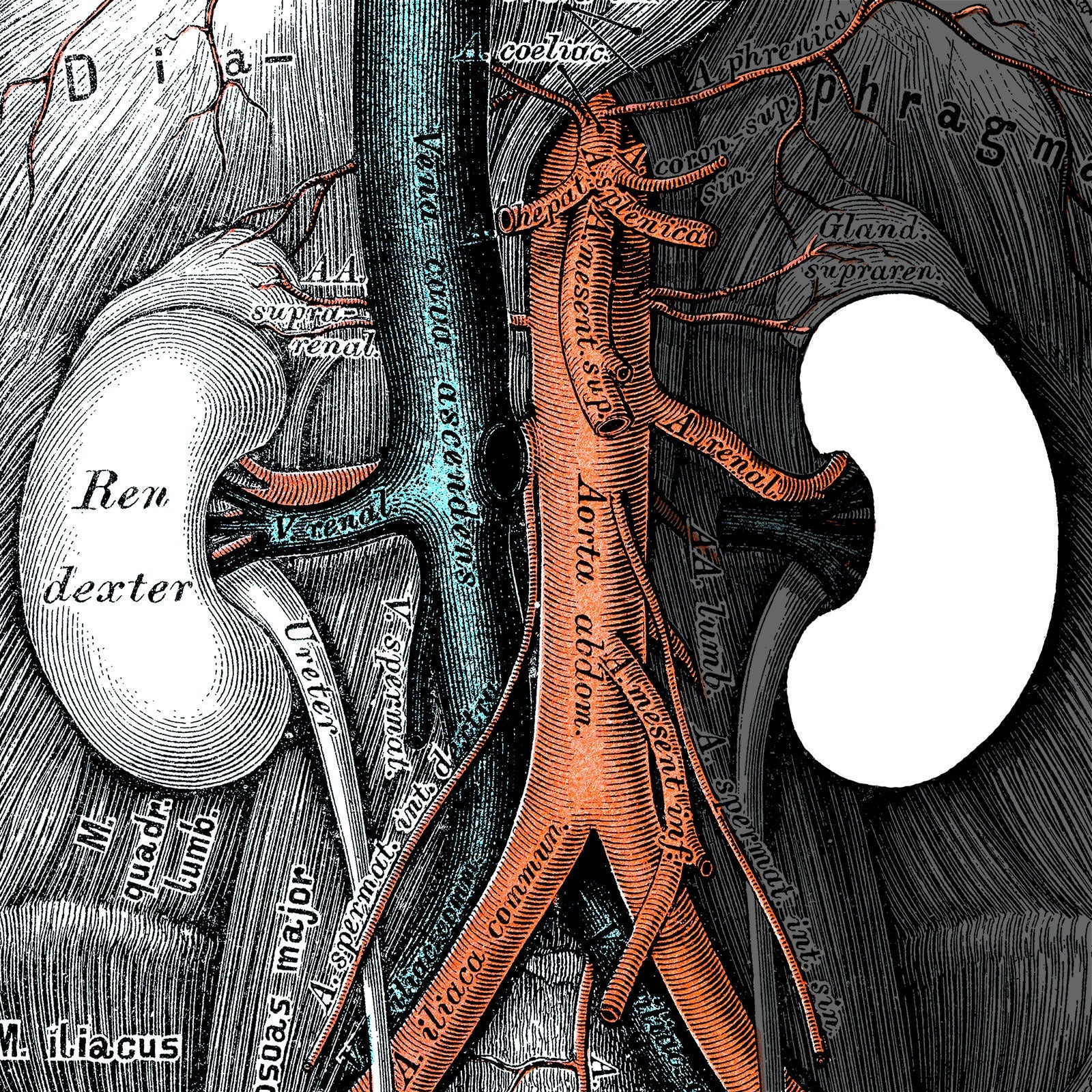

Kidneys are unsung heroes of the body. Their miles and miles’ worth of delicate meshwork compose a complicated filtration system that metabolizes cellular waste, maintains blood pressure, and regulates acid buildup. When kidneys fail, all these essential processes stop. Water, chemicals, pollutants—everything in urine—get stuck. That can leak into the lungs and cause the body to balloon and swell. It can interrupt communication between cells. It can make a heart stop.

Knowing how well a patient’s kidneys can clean their blood is important for countless medical decisions, from diagnosis of kidney disease to proper medication dosing. It’s difficult to calculate kidney function quickly—doing so once required patients to store a full day’s worth of urine in their refrigerators so physicians could look at what the kidneys had successfully filtered out of the body. In 1999, a major study in the Annals of Internal Medicine painstakingly measured the GFR of more than 1,500 patients to develop a model that could more easily predict how well the kidneys were working using just a rapid blood test and some math; the resulting number is known as the estimated GFR, or eGFR. The equation—which has been formally cited more than 15,000 times in the literature—was quickly folded into medical practice and remains a standard of care today.

The formula focuses on creatinine, a byproduct of muscle activity and one of the many things that the kidney is supposed to remove from blood. Generally, when creatinine levels in a patient’s blood are high, it signals that the kidneys are struggling to do their job of filtering toxins; this makes creatinine levels something of a proxy for overall kidney health. But things get more complicated when you consider that people vary in shape and size, have different muscle mass in their bodies, and therefore have different amounts of creatinine in their blood to start with.

Indeed, during development of the mathematical model, authors found that overall, the population of Black patients in their study had higher levels of creatinine in their blood compared with the group of white patients. The authors reasoned this was likely because “on average, black persons have higher muscle mass than white persons.” They added a race-based coefficient to correct for what they assumed must be naturally high levels of creatinine in Black patients, recommending that doctors inflate the eGFR of patients by 21 percent “if Black.”

This eGFR multiplier can make Black patients with kidney disease appear healthier than they are. It means that Black patients have to reach higher levels of kidney disease before they are considered sick enough to qualify for certain treatments or interventions. The adjustment is the reason Jordan wasn’t able to register on the kidney waitlist after his first transplant evaluation years ago.

“I usually don’t think about it much,” Jordan tells me of his shrunken kidney. He’s more focused on studying principles of psychology and being a good dad to his dogs—a beagle named Jake and a rescue mutt with a torn meniscus named Abby—than his illness. The one thing that does bother him, though, more than the hospital visits, infections, surgeries, and convulsions that he’s had in his life, is the idea of being on dialysis.

Patients with severely crippled kidneys can extend their life by participating in dialysis—a process in which a machine does the work that a patient’s kidneys can no longer manage. In addition to consuming large swaths of a patient’s life—they usually must be tethered to the device for hours, several times a week—dialysis comes with its own set of serious health risks. Creating an access point strong enough to withstand continued dialysis requires surgery to stitch a vein and artery together, and this procedure can cause a slew of complications including heart failure, nerve damage, and dangerous clotting or bleeding. What’s more, constant instrumentation introduces bacteria into the body that can cause life-threatening infections in already immunocompromised patients.

Men who begin dialysis between age 20 and 24—as Jordan is on track to do—on average will only live until they’re 38 or 42. But a 20-to-24-year-old who receives a kidney transplant can expect to live for 44 more years—more than double, and long enough to collect Social Security. For Jordan—or DogLoverJordy as he’s known online—that might mean 26 additional years to foster injured pups. Twenty-six more years to pursue his dream of becoming a counselor for children.

When the kidney isn’t doing its job, every other organ gets hurt. Sodden with fluid and stuffed with toxins, the heart bloats. The lungs doze in froth; bones weaken into lace; the blood can forget how to clot and thin into the color of sour oranges. Waiting for a kidney transplant doesn’t mean just dealing with a sicker kidney later on; it often means dealing with a sicker everything.

Ideally, every person with seriously sick kidneys would be able to receive a transplant before having to be hooked up to a dialysis machine to stay alive. But the organ is incredibly scarce, which is why getting in line for one is so tightly regulated in the first place. Even being on the list is hardly a guarantee. Though 100,000 people in the U.S. are registered on the waitlist, only about 17,000 kidney transplants happen annually. Each year, nearly 5,000 registered patients die while waiting for a kidney. Another 4,000 people will just slide off the list, losing their spot because they’ve become too ill to receive an organ.

Fifteen people die while waiting on the kidney transplant list every day. On average, nine of those dead will be Black.

I want to fight inequities like this during my career as a physician. We need to deliver more equitable care, and that commitment involves understanding how medical systems are perniciously structured to shuttle the best care to white people. Last June, I was searching for an epidemiologist to help me analyze racial inequities in kidney transplants and was connected with Jay Kaufman, a health disparities scientist who graciously mentored me over the pandemic months. In our conversations, he mentioned, then introduced me to Jordan—his nephew.

I was immediately taken by Jordan’s story. It’s an illuminating example of how racism is alive and burrowed within medicine, and it’s also a story of urgency. I’ve been an emergency medicine physician for only two years, and that’s already been enough to learn that bad kidney disease can leave both patient and provider quivering. The deadliness of kidney failure is so recognized that when an ambulance patch crackles over the radio announcing an incoming sick dialysis patient—we’ll be there in five—I can feel the whole team tense.

Jordan’s grandmother Joyce Kaufman is a white woman who has spent her life as a nursery school teacher and mother to biracial foster children, including Jordan’s mom, Jessica. Jordan is her buddy. Because his health issues made it impossible to enroll him in day care, Jordan has been at Joyce’s side since the day he was born.

Joyce remembers finding out about the GFR race adjustment at a transplant evaluation appointment in 2016. After asking about her grandson’s lab results, a nurse practitioner told her the computer was having a “difficult time” because it didn’t know whether to evaluate Jordan as Black or white.

Kidneys are not white or Black; there are, in fact, no genes, physiologic traits, or biological characteristics that distinguish one race from another. “If you know anything about human genetic diversity and the commonality of human physiology, it just doesn’t make any sense that the simple equation could involve a binary race variable,” says Jay Kaufman. “It’s so illogical that it has to be false.”

Yet, race-based adjustments alter reality for patients like Jordan. A patient’s eGFR determines not just whether he is allowed on the transplant list, but what stage of care he can get: Medicare-covered nutritional therapy and reimbursed kidney disease education kick in at an eGFR of 50; referral to a doctor that specializes in kidney disease is guarded by an eGFR threshold of 30, as is referral to formal transplant evaluation, with the threshold of 20. Again and again, the race-based inflation can delay when Black patients meet cutoffs for resources that offer real survival benefits: Kidney disease patients who have been cared for by kidney specialists, for example, have lower rates of hospitalization and death.

If the race adjustment were eliminated from medical practice, a third of Black patients with kidney disease would be reclassified to a more severe stage, and thousands of Black Americans would receive a diagnosis of kidney disease for the first time, according to a study completed by researchers at Harvard University published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in October. This increases opportunity for preventive medicine and early treatment, which is important because kidney disease is often silent until the damage is already done.

Because he was born sick, Jordan has been monitored with monthly blood tests for years. But those who don’t receive diagnosis of kidney injury in a timely manner lose out on this extra care, which can increase the risk of “crash” dialysis, wherein patients with no previous preparation suffer severe kidney failure complications like heart arrhythmias, bleeding issues, strokes, or seizures and are urgently placed on dialysis for survival. I’ve seen this done in the emergency department several times. It’s shocking to everyone involved when a patient first learns about their kidney disease the day they are rushed to the hospital for kidney failure.

Now, an old assumption about Black bodies is preventing Black people from receiving timely diagnosis and access to treatment. When authors of the 1999 study added the race adjustment, they didn’t prove the idea that Black patients have higher levels of creatinine due to higher muscle mass. In fact, they never actually measured muscle mass. What’s more, they made this conclusion about fundamental racial difference without controlling for socioeconomic status, education, geography, or other diseases that affect kidney function, like diabetes and high blood pressure.

Our country has been filled with racial inequality from the start, and it’s unsurprising that racism gets under the skin to jeopardize the health and well-being of Black bodies. Racial inequities that limit where people of color live, eat, pray, and breathe can all influence how effectively the kidneys churn urine, producing health disparities in kidney disease and beyond. Other factors, like the amount of protein in a patient’s diet, athletic activity, and dehydration can all directly affect the level of creatinine in someone’s blood. But the authors didn’t look into any of those things and assumed the heightened creatinine had a simple explanation, in increased muscle mass. The authors stopped their inquiry and conclusions short.

The fact that the original study even included Black patients at all was progress, explains Lesley Inker, a nephrologist and one of the pioneering researchers behind GFR estimation equations. Usually, medical studies weren’t—and still aren’t—built on robustly diverse data. The precursor to the 1999 formula, for example, was developed based on data from only 249 white men. But while including a diverse set of patients in medical studies is critical to delivering accurate and ethical care, it’s not because Black bodies are biologically different.

The idea—and evidence—that Black people have more muscle mass than their white counterparts across the board is “total crap,” says Joel M. Topf, a clinical nephrologist at Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine. He notes that while such adjustments may be informative at a population level, they are “lousy” for individual evaluations, not to mention “easily perceived as racist.” Joyce Kaufman recalls that Jordan’s pediatric urologist once called the eGFR adjustment “a holdover from slavery.” She cackles at the idea that while Arnold Schwarzenegger’s lab work will remain unadjusted for increased muscle, Jordan’s will be recalculated for brawn. “Let me tell you,” she laughs, “this kid looks like a sewing needle.”

In everyday conversation and even in medical scholarship, racist imaginations of Black bodies cause harm. Stereotypes—that Black people have bigger butts, thicker skin, aggression stamped into their brains—might seem antiquated and obviously ludicrous, but they are constantly mobilized in service of dehumanization. Think about how assumptions of greater muscle mass reinforce Black people as second-class citizens primed to do labor. Through eGFR modifications and other race-based recommendations that judge the wombs, bones, brains, lungs, bladders, and hearts of Black people differently, racialized tropes have been subtly knit into medical algorithms and are buried in the decision-making of doctors every day.

When Jordan’s family discovered he wasn’t going to be listed for kidney transplant because of a race-based modification, they protested the 4-point addition. They brought up that Jordan is three-quarters white. If a white version of Jordan had a GFR of 17, and a Black version has a GFR of 21, wouldn’t it follow, even with this sort of hackneyed race math, that actual Jordan has a GFR of 18, placing him below the threshold and onto the transplant list?

It didn’t matter. The doctors in charge of Jordan’s first transplant evaluation—in a disturbing echo of the “one drop” rule—decided he was Black.

Joyce drove Jordan hours across town, to a different hospital, to see if different doctors would treat him as a white child. They said no. Years later, as they wait in a holding pattern for Jordan’s GFR to decline further, Joyce wonders if she should have just listed Jordan as white—after all, “it’s not like there’s something in his blood test to show differently.”

Jordan’s appraisal of the GFR race adjustment is simple: It doesn’t feel fair, and it doesn’t make sense.

A lot of people agree with him. And as researchers, trainees, and physician advocates across the nation draw more attention to the flaws inherent in basing medicine on racial classifications, the field is changing. In the past four years, Massachusetts General Hospital, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, and the University of Washington Medical Center are among several health care institutions that have abolished the race adjustment in calculation of eGFR. This summer, the American Society of Nephrology and the National Kidney Foundation established a joint taskforce to reexamine the use of race coefficients in their guidelines, and the House Ways and Means Committee publicly urged professional medical societies to question race-based practices.

Jay Kaufman is confident that race adjustments will be “relics” in the near future—that tomorrow’s physicians will be more sensible, more conscious of both equity and the scientific facts of racial formation. Topf, the clinical nephrologist, agrees that the GFR race adjustment is on its way out and notes he’s “not going to shed any tears when it’s gone.” In the meantime, he says, physicians should stop focusing on a single GFR number and focus on the whole patient in front of them.

Still, the measurement has its defenders. Inker, a prominent eGFR researcher, says she feels saddened and shocked when she hears stories like Jordan’s but isn’t yet sure if she believes hospitals should drop the adjustment. Inker’s main argument—and that of other experts in favor of keeping the GFR race coefficient—is that more Black patients could be harmed than helped by its sudden removal. As Neil Powe explains in an essay published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, abandoning the race adjustment could mean fewer Black people would be able to donate their kidneys—since the removal of the inflation could leave potential donors with eGFRs too low to qualify their organs as healthy enough for transplant. Eliminating the multiplier might also affect the number of Black patients able to receive certain pharmaceuticals—like commonly used diabetes medications and antibiotics—that are restricted because they can cause injury in patients with too-sick kidneys.

But this weighing of risk/benefit misses the fact that the current, race-adjusted eGFR formula could be traded in for something else entirely. Both Kaufman and Topf note the utility of calculating cystatin C, which is a validated test of kidney function that is more precise than current creatinine-based estimations of eGFR—and doesn’t take race into consideration at all. Some physicians wave aside use of cystatin C by arguing that the test is 100 times more expensive than the cost of measuring creatinine—the blood test used to calculate current estimations of GFR. This is true, though we’re still talking relatively small amounts: The creatinine test costs 2 cents, while the cystatin C test costs $2. A dollar and change seems like a worthwhile price for greater precision in life-or-death decisions, and it’s likely that the test would become less costly if it were routinized as a standard of care.

Technically, Jordan’s evaluating kidney doctor could have gotten him onto the list years ago. Though most American laboratories use the race-based 1999 formula to calculate kidney function by default, when transplant nephrologists submit numbers to prove a patient qualifies for the waitlist, they can use any recognized eGFR formula in their documentation to support their case. William Asch, the director of pre-transplant operations at Yale School of Medicine (who was not involved in Jordan’s care), explains that he sometimes calculates his patient’s kidney function with multiple formulas to see “if one of them happens to get a better number.” It’s clear that Asch, and transplant nephrologists across the country, want to advocate for their patients and get them on the list as quickly as possible.

To that end, Inker explains that nephrologists should see calculation of GFR as a “first line test that’s appropriate for many different situations, but not all of them.” But that doesn’t mean that doctors—a majority of whom are white—will necessarily think to try eliminating the race adjustment on their own. When I ask Asch if he ever submitted a non–racially adjusted GFR to help a Black patient register on the list faster, he admits that he’s “never thought to not use the race correction,” even though he could.

That the eGFR could be modified or replaced by individual doctors is part of Inker’s defense for keeping it (though the example she gives for when second-line confirmatory tests might be necessary is not regarding race, but when a patient has a limb amputation). In practice, that kind of modification for race is very rare. The system, then, favors patients with doctors who are well-read on the inequities associated with race-modifiers and have the time and energy to modify the formula for their patients—or patients who are able to educate their doctors in the first place.

Most patients don’t have an eminent scholar of racial inequity—and the current president of the Society for Epidemiologic Research—for an uncle. Jay Kaufman acknowledges that his expertise on racialized medicine offers his family an advantage that many others don’t have. “It’s empowered my mother to be much more assertive and say, ‘I refuse to accept this, because this is not based on any kind of meaningful scientific theory.’ ” But even this deep knowing of how unfair the system is hasn’t been enough to fix things for Jordan. When Joyce Kaufman brought up her concerns about the race multiplier to Jordan’s transplant team, the transplant surgeon didn’t even respond to her questions. “I think doctors are very reluctant to change their way of doing something, because it means that what they did before was not right,” she says.

Jay Kaufman supports his mother’s advocacy but admits that having individual patients come to their doctor’s appointments with printed medical studies isn’t necessarily conducive to changing physician behavior, because doctors simply follow racialized algorithms set forth by more authoritative bodies like professional medical organizations. (If that’s the case, Joyce says, “Then change the damn medical books!”) Jay’s strategy to combat race-based medicine dovetails with his professional role as an epidemiologist and scientist: He thinks the way to create change is to harness population data to create new standards of care and practice guidelines that physicians will have to learn to receive continuing medical education credits.

Jordan’s previous pediatric urologist (who was not able to be reached for comment for this piece) told the Crowleys and Kaufmans not to worry. He acknowledged the inaccuracy of the adjustment, and reassured Joyce that the team “won’t let anything bad happen to Jordan.” But missing out on an earlier spot on the transplant list is, already, bad for Jordan.

If not for the racialized adjustment, Jordan would have qualified for the kidney transplant when he was first evaluated. Jordan and Joyce’s lives would feel a little bit more secure, more stable; an important next step in his treatment would already be underway.

For now, Jordan is still waiting. Along with so many other Black patients, he keeps waiting.