Don't Cut Social Security—Double It

Fiscal cliff chatter about slashing the venerable program ignores its fundamental potential and underlying strength.

As the nation tiptoes closer to the fiscal cliff, a frightening number of leaders on both sides of the political aisle seem ready to push poor, beleaguered Social Security over the edge. Not only would that be a huge mistake for the nation's future, but these leaders show a dreadful misunderstanding of the new challenges faced by the U.S. retirement system. Particularly in the aftermath of the largest economic collapse since the Great Depression, none of the proposals on the table are grappling with some stark economic realities. How we settle this New Deal legacy will decide fundamental questions about what kind of society America will be for generations to come.

Here's the dilemma that the United States faces. Since World War II, individual retirement has been based on a "three-legged stool," with the three legs being Social Security, pensions, and personal savings (the latter primarily centered around home ownership). But two out of three of these legs have been chopped back to blunted pegs, leaving the retirement stool as an unstable, one-legged oddity.

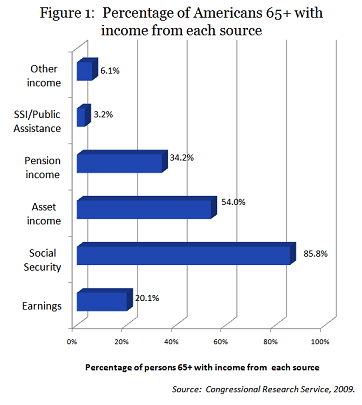

Pensions have always been the least broadly distributed asset, with only a third of elderly Americans (those 65 and over) earning pension income, a percentage which has been declining dramatically in recent years. A bit over a majority of these older Americans have income from personal savings, most of that residing in the value of their homes. But 86 percent receive Social Security payments (see Figure 1).

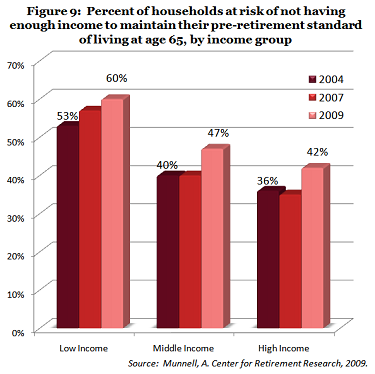

Even before the Great Recession, 40 percent of middle-income and 53 percent of lower-income Americans already were at risk of having insufficient retirement funds. But the economic collapse has taken its toll on two out of three of Americans' primary retirement resources: pensions and savings/investment in a home.

Already Off the Cliff: Pensions, Private and Public

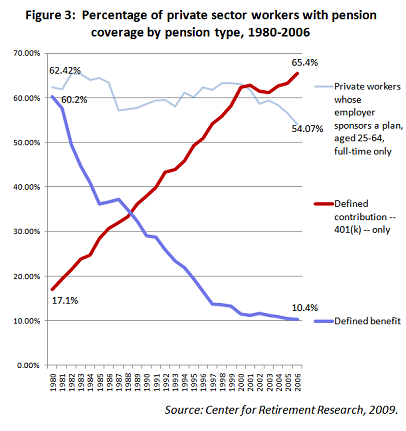

American pensions were some of the hardest hit in the world by the Great Recession, falling in value by over a quarter in 2008, with only modest recovery since then. But private pensions already had become a less steady leg of retirement security prior to the recent recession. Since the early 1980s, businesses have gradually shifted responsibility for pensions onto workers, with predictable results. In 1981, approximately 60 percent of private sector workers were covered by a pension with a guaranteed payout. Today only about 10 percent of private sector workers have guaranteed payout pensions. Meanwhile, 401(k)-type retirement contribution plans have gone from covering only about 17 percent of the private workforce to about 65 percent today (see Figure 3).

401(k)s and other defined-contribution plans have turned out to be an unreliable pillar of retirement security, not only because they don't provide as secure a net but because many Americans are pretty lousy at managing their investments. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that more than one-quarter of baby boomer households thought "hardly at all" about retirement and that financial literacy among boomers was "alarmingly low." Half could not do a simple math calculation (divide $2 million by five) and fewer than 20 percent could calculate compound interest.

In the public sector, most workers still are covered by guaranteed payout pensions, but the number of public sector workers has declined dramatically in recent years, accelerating as a result of the Great Recession. There are now a million fewer federal employees than when Ronald Reagan left office, and public sector employment is at a 30-year low.

In addition, states have funded only about 80 percent of their pension liability, leaving a $3.32 trillion funding gap. Ohio and Rhode Island are in the worst shape, having underfunded their pensions by almost 50 percent of their gross state product. Other liabilities, such as retiree health and dental insurance, also are underfunded. City governments similarly are plagued by underfunded pensions, with Los Angeles underfunding its public pension liabilities by $3.53 billion, with an additional $2.43 billion owed for other employment benefits such as healthcare. As of June 2009, New York City public pension programs had liabilities that exceeded their assets by $39.9 billion with an additional $65.5 billion owed for other benefits.

So both the private and public components of the U.S. pension system are under severe strain, as the Great Recession combined with pre-recession patterns of rising inequality and a diminishing social contract have taken their toll. With fewer workers covered by pensions, this leg of the three-legged stool of retirement security is too short -- and growing shorter.

Already Off the Cliff II: Home Ownership and Personal Savings

Now let's examine the second leg of retirement well-being, personal savings centered around homeownership. For tens of millions of Americans, security in their elderly years has been directly linked to the value of their homes. Yet the rupture of the housing bubble illustrated in dramatic fashion the danger of over-reliance upon ever-rising home values for retirement security.

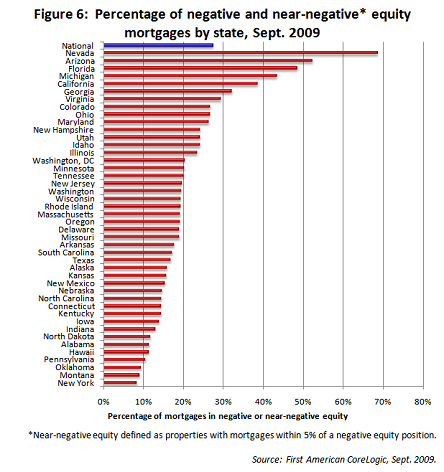

The Federal Reserve has estimated that homeowners lost approximately $8 trillion in home equity during the Great Recession, a 53 percent drop in the overall value of the national homeownership stock. About 14 million Americans -- about 28 percent of all homeowners -- are still underwater today, owing more on their mortgage than their home is worth. These homeowners are, in effect, flat broke if they have no other accumulated savings or retirement vehicle (see Figure 6, which shows the percentage of mortgages that are underwater).

This has been devastating for Americans' retirement well-being because home ownership accounts for a large proportion of assets for so much of the population. As of 2008, only the top two income quartiles had accumulated enough equity from financial assets and pensions to weather the bursting housing bubble. The bottom 50 percent had not saved enough outside their homeownership to avoid severe wreckage to their retirement plans.

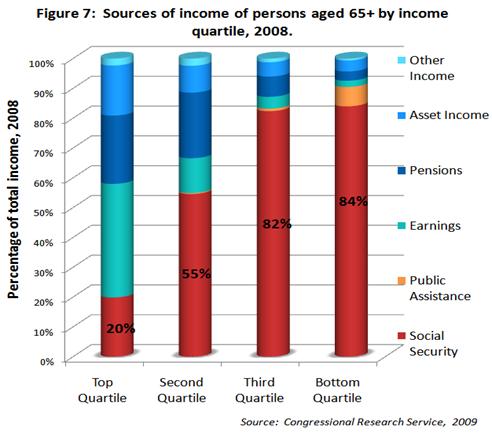

Thus, the second leg of the three-legged retirement stool has been broken down to a nub. And with home prices unlikely to recover soon, this loss in equity has significantly reduced the economic security of the lower and middle classes, which are less likely to have pensions and other assets such as private savings (beyond homeownership) to sustain them. Indeed, the bottom two income quartiles for those aged 65 and over depend on Social Security for at least 80 percent of their income, but even the second richest quartile still depends on Social Security for over 50 percent of its retirement income (see Figure 7).

In short, the collapse of the housing bubble when combined with the slow erosion of America's pension system has hacked away two of the three legs of the retirement stool. In the future, the vast majority of baby boomers and other retirees will be almost completely dependent on the single leg of Social Security for their retirement. The retirement stool no longer is stable and secure, and suddenly Social Security, which always has been viewed as a supplement to private savings, is the only leg left for hundreds of millions of Americans.

Financial experts say it will take a monthly retirement income of about 70 to 80 percent of pre-retirement income levels -- as well as $200,000 to $300,000 in personal savings -- for the average American to have a secure retirement. Yet most older Americans have saved only a fraction of that. In 2010, 75 percent of Americans nearing retirement age had less than $30,000 in their retirement accounts. About half of all Americans are at risk of not having sufficient retirement income, and three-fifths of low-income households are at risk of not having sufficient income to maintain their pre-retirement standards of living at age 65 (see Figure 9).

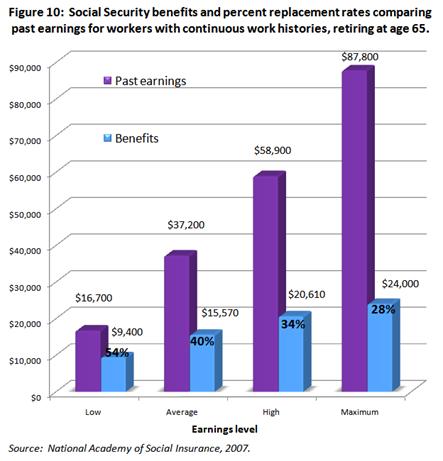

A single legged stool might be sufficient if that single leg was robust enough to stand on its own. But Social Security currently provides much less than the 70 to 80 percent of pre-retirement income needed to maintain pre-retirement standards of living. It is estimated to replace only about 33 to 40 percent of pre-retirement income for the average wage earner, compared to other nations like Germany or France where it replaces 70 percent (see Figure 10).

So the one-legged stool of the U.S. retirement system is looking like a rather odd piece of furniture, one that is increasingly unstable. For more and more Americans, the dream of a secure retirement is threatened. New solutions are needed to provide security to retiring Americans, both now and in the future.

The Solution: "Social Security Plus"-- Expanding Social Security

An expansion of the Social Security retirement system -- one of the most successful and popular social programs in American history -- that converts it into a more robust retirement system would build upon the most stable component of the current system. Social Security already provides the major means of support for two-thirds of America's retirees. Since its New Deal inception in the 1930s, and gradual expansion in subsequent decades, Social Security has become a mainstay of retirement security, firmly rooted in America's cultural and economic landscape (as leaders like President George W. Bush discovered when he tried to privatize it).

The real problem with Social Security is not, as its critics say, that it is underfunded. Contrary to gloomy predictions, the program is on solid financial footing, with the Congressional Budget Office projecting that Social Security can pay all scheduled benefits out of its own tax revenue stream through at least 2037. The bigger problem is that Social Security's payouts are so meager -- far too low for the program's new role as America's de facto national retirement system. It only replaces about 33 to 40 percent of a retiree's average final wage, which is simply not enough money to live on when it is your primary -- perhaps your only -- source of retirement income.

The gritty reality that the Obama administration and House Republicans must face is that the vast majority of America's retirees cannot afford to watch them hack off part of the only leg that remains of the three-legged stool. Quite the contrary, we should make that leg more robust by doubling the current Social Security payout, and turning it into a true national retirement system called "Social Security Plus." Doing so not only would be good for American retirees, but also would be good for the greater macro economy.

Doubling Social Security's individual payout would cost about $650 billion annually for the approximately 53 million Americans who receive benefits. Here's how to pay for it.

Step 1. Lift Social Security's payroll cap that favors the wealthy.

Currently Social Security only taxes wages up to $106,800 a year, and any income earned above that is not taxed. The net result is that poor, middle class, and even moderately upper middle class Americans are taxed 12.4 percent (split between employee and employer) on 100 percent of their income, but the wealthy pay a much lower percentage. Millionaire bankers effectively pay a paltry 1.2 percent.

Making all income levels pay the same percentage -- which is how Medicare works -- is popular with Americans according to opinion polls, and would raise about $377 billion toward the $650 billion needed to double the Social Security payout. As a candidate in 2008, Barack Obama stated that he supported raising the cap on the Social Security tax to help fund the program.

Step 2. Cut out the business deduction for employees' retirement plans.

With all Americans receiving Social Security Plus, employer-based pensions would be redundant, so businesses no longer would need the substantial federal deductions they currently receive for providing employees' retirement plans. These deductions total a substantial $126 billion annually.

These two steps alone would provide three-fourths of the revenue needed to double Social Security's payout.

Step 3. Cut or reduce other deductions that disproportionately benefit top income earners.

Other possible revenue streams should include ones that would reduce or eliminate unfair deductions in the tax code which currently allow the top 20 percent of income earners to reap generous deductions that barely help most low and moderate income Americans. These include deductions for private retirement savings, health care, homeownership and education.

Only higher income individuals have enough earnings to divert for savings or investments that allow them the luxury of enjoying considerable tax deductions for their 401(k)s, IRAs and pensions. The poor and middle class rarely can take advantage of these sorts of deductions because they don't make enough income to benefit from itemizing deductions on their tax returns. As Josh Freedman pointed out recently in The Atlantic, in 2011 less than 30 percent of all filers itemized their taxes, and more than 80 percent of the benefits from itemized deductions went to individuals in the highest income quintile.

The same goes for the much vaunted home mortgage interest deduction. Those with annual incomes over $100,000 dollars received nearly 75 percent of the benefit from the home mortgage interest deduction in total dollars. Most middle class individuals would not see any increase in their taxes if the mortgage interest deduction were eliminated. Instead of buying a home as part of their retirement plan -- which we now realize can be a risky undertaking -- more people could put their money into Social Security Plus. Eliminating the mortgage interest deduction would raise another $100 billion to pay for Social Security Plus, and eliminating the other deductions would bring us close to the $650 billion mark.

An expansion of Social Security not only would be good for America's retirees, it also would be good for the broader macroeconomy. It would act as an "automatic stabilizer" during economic downturns, keeping money in retirees' pockets and stimulating consumer demand, especially since low and middle income people are more likely to spend an extra dollar on goods and services than are affluent individuals. Social Security Plus also would help American businesses trying to compete with foreign companies that don't have to provide pensions to their employees, since those countries already have national retirement plans.

Moreover, unlike private pensions, Social Security benefits are portable when changing from one job to another. Every worker could contribute to her or his own retirement pension no matter where she or he worked. Those savings could be directed into a Social Security Plus system with investments restricted to Treasuries, instead of handing it over to mutual or pension fund managers who gamble on the volatile stock market with future retirees' money (there is no evidence that the typical investment fund manager consistently beats the average return on Treasuries). And this system would be broadly fair, since even those higher income Americans who are having some of their tax deductions reduced would see part of it returned to them in the form of a greater Social Security payout.

In short, Social Security Plus would provide a stable, secure retirement for every American and contribute greatly toward a solid foundation from which to build a strong and vibrant 21st century economy. All Americans should have retirement benefits they can count on, not the crumbling casino of retirement overseen by the same Wall Street bankers and financial managers who drove the U.S. economy off the cliff.

This article is adapted from the author's study for the New America Foundation.